Motivation Matters, When You’re Paddling Across Florida

- Written by Tom Fucigna Jr.

- Published in Journeys

- Comments::DISQUS_COMMENTS

Jake Portwood, a 38-year-old native Floridian, describes himself as “a husband, father, firefighter, and competitive standup paddler.”

2024 was a busy year, full of accomplishments on the water. In Toronto, he paddled in the Eastern Canadian Championships against the best in North America and took first place. He was first in the technical course in the South Carolina Goat Boater series, won the infamously rough Key West Classic 12-mile around-the-island race, took two top 20 finishes in sprint and technical events at the World Championships in Sarasota, Florida, and won the Low Country Boil in South Carolina to claim the title of USA SUP National Champion.

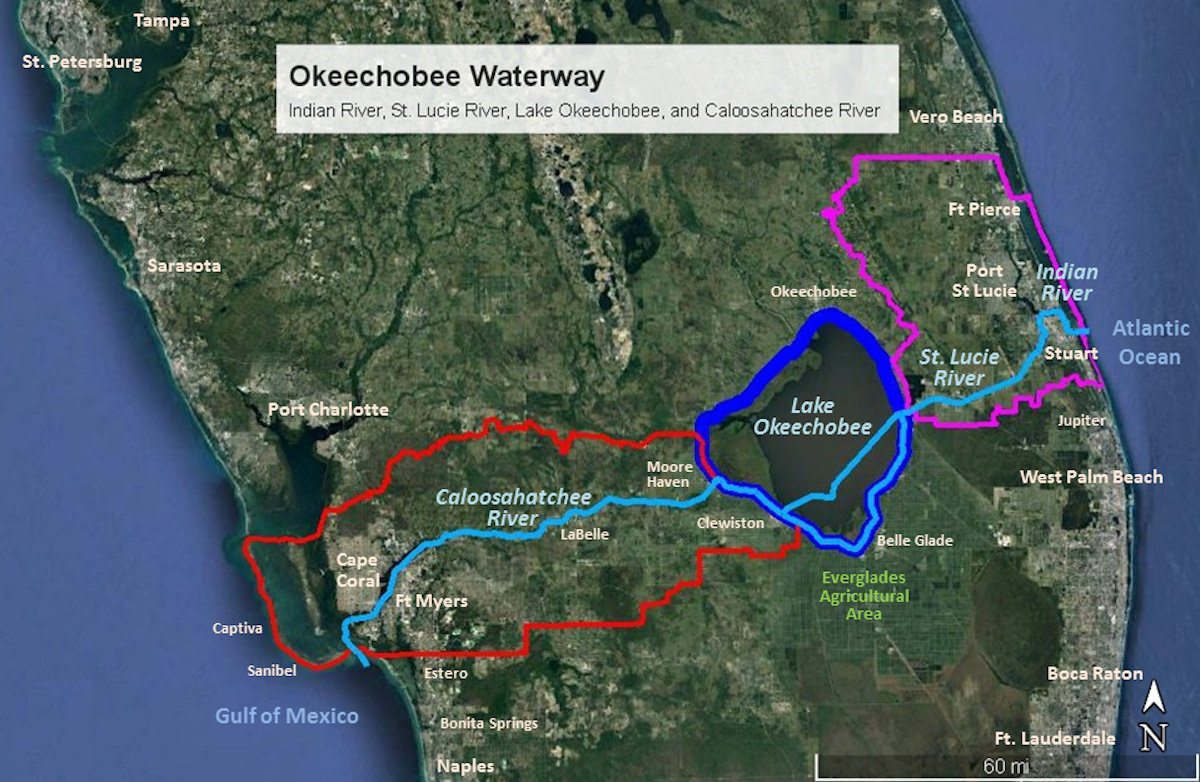

Great stuff, but his most notable achievement was a slightly longer course - the Okeechobee Waterway, which runs from Florida’s Atlantic Ocean coast to the Gulf of Mexico.

Lake Okeechobee is the largest lake in the southeast U.S. It’s about 30 miles wide, but the average depth is only nine feet. “Lake O” is also literally at the center of a major water quality crisis. South Florida has been described as a giant plumbing system, designed to direct, hold, and/or dispose of water as dictated by a variety of user goals, from agriculture and flood control to environmental sustainability and wildlife habitat preservation.

Historically, water flowed through meandering drainages into Lake Okeechobee, and then continued southward from the lake, through a vast swamp of pond apple trees and a broad shallow marsh that has come to be known at The River of Grass – our Everglades - until it met the tide in Florida Bay. That journey purified every drop of water along its journey to the bay.

Today, areas north of the lake have been drained and developed for housing or are managed as cattle pasture, and the fertile swamp and much of the marsh south of the lake has been drained and is intensively managed for monocultural agriculture. Lake O is surrounded by a giant levee that protects the surrounding towns from flooding, and allows water to be pumped to and from agricultural areas during the dry and wet seasons. Only a fraction of the lake water is routed south, and there’s less than is needed to sustain the southern Everglades and Florida Bay. Instead, when the lake level gets higher than the levee can safely contain, massive volumes of nutrient-laden water are shunted east and west through flood gates and man-made canals. Lake water rushes east to the St. Lucie River, and west to the Caloosahatchee River, and then deluges the coastal estuaries. The St. Lucie River drains east to the Indian River Lagoon, a state-designated Aquatic Preserve and part of the National Estuary Program, and then to the Atlantic Ocean.

Lake Okeechobee. | Photo: Shutterstock

Lake Okeechobee. | Photo: Shutterstock

To the west, the Caloosahatchee River drains to the Pine Island Sound Aquatic Preserve and then into the Gulf of Mexico. The effluent that enters these valuable ecosystems is nothing like the water that once meandered to Florida Bay. The problems associated with Lake O releases include drastic overnight changes in salinity that stress and can kill non-mobile sea life such as oysters, and toxic algae blooms fueled by high nutrient levels that can poison fish and marine mammals such as manatee and dolphins, and stifle seagrass meadows which are vital to the estuarine ecosystems and fisheries.

Jake “had been talking about paddling the waterway” since his early days of racing. It was “a route that looked interesting” that he thought would be "fun" and so he began organizing, and training for, the first ever standup paddleboard crossing of the Okeechobee Waterway.

What started as an adventure scheme morphed into something more. “Growing up in South Florida I would visit and fish on Lake O and heard about the discharges, but I didn’t know much about the issues, or the impact that diking the lake had on the Everglades.” Then, “after moving to Stuart (located on the St Lucie River), I witnessed those effects personally. All the Lake O discharges being sent east drain to Stuart and ultimately the Atlantic Ocean.”

Jake’s perspective shifted. “I began to educate myself on this topic and spoke with two good paddle buddies, Packet Casey and Blake Carmichael” and then “a paddle that I wanted to do for fun turned into a Mission. We decided to use this ultramarathon paddle to raise awareness and funds to fight against our Lake Okeechobee crisis.”

Jake’s perspective shifted. “I began to educate myself on this topic and spoke with two good paddle buddies, Packet Casey and Blake Carmichael” and then “a paddle that I wanted to do for fun turned into a Mission. We decided to use this ultramarathon paddle to raise awareness and funds to fight against our Lake Okeechobee crisis.”

They started planning a four-day, 155-mile paddle from the mouth of the St Lucie Inlet, on the Atlantic coast, up the St Lucie River and canal to Lake Okeechobee, and then – after crossing the lake - down the Caloosahatchee canal and River to Fort Myers, on Florida’s Gulf coast.

Jake “planned out the route and logistics, and then began seeking sponsors and fundraising. We teamed up with Captains for Clean Water, a nonprofit organization from Fort Myers, and obtained some great sponsors including Flying Fish paddleboards, Blueline Surf & Paddle Co., and Pink Shell Resort. With their help and about 100 other donors we raised over $10,000 to support local non-profits that are leading the battle for clean water.”

The planning was not simple. “Logistically, this trip was pretty difficult and had many obstacles, but we had a great team that got us through everything. There are five locks within the 155-mile Waterway, and they only operate from 7:00 AM to 4:30 PM, which meant we had cutoff times every day. The Waterway is also pretty desolate when it comes to accommodations. We considered camping, then decided a comfortable bed was important after paddling 40 to 45 miles a day, but finding enough room for our team of six was tricky. The only part of the planning that came easy was our support vessel. Blake’s dad Robert has a 41-foot Solace which worked perfectly for all the equipment and supplies that we needed to bring. Plus, with Captain Robert and Big Doug at the helm with all their boating experience, we had nothing to worry about.”

|

|

|

Day 1 Paddling. | Photos: Logan Graham

This was not a relay - Jake, Packet and Blake each paddled the entire distance, side by side or taking turns leading, with no assistance from their support vessel. The Day 1 paddle distance was 41 miles. The trio “had the incoming tide with us until about mile 10, and then the two to three mph discharge current was against us the remaining 31 miles. We had to portage our boards around the St Lucie lock, which included a tough climb up an old dock. The closer we got to the lock the more the water quality deteriorated. The water was so dark that you couldn’t see your paddle after it broke the surface of water, and we saw green algae and clumps of dead grass everywhere. Even the smell was unwelcoming. We didn’t see much wildlife, and almost no marine life. I think even the alligators were grossed out, because we only saw about five during the entire 155 miles. Day 1 was tough, but we all powered through, only taking a short break about every 10 miles to refill our hydration packs and get some food.”

Day 2, the lake crossing, totaled 36 miles. Jake said it was “my biggest concern, but we lucked out and had a slight tail wind to assist us. It was an eerie feeling, reaching the middle of the lake and not being able to see land in any direction, making you realize how large Lake O really is. And again, still seeing bits of algae everywhere with black water. After we crossed the lake, we paddled through a beautiful narrow canal and saw lots of birds and even the famous white pelicans.

|

|

Photos: Logan Graham

Day 3 delivered the team’s biggest setback. “On the second night, we stayed at Roland Martin’s Marina in Clewiston, along with about 60 bass fishermen who were there for a tournament, and we couldn’t fit our boat into the first lock opening, which delayed us by about an hour. Once we got through the lock we were greeted by dense fog, which forced us to motor at idle speed back to our previous day’s stopping location, causing another delay. The Day 3 route was supposed to be easy paddling, because we’d be paddling down current with the lake water discharge, in the Caloosahatchee River, but, since we were delayed about two hours, we hit a solid headwind at about 15 miles into our planned 45-mile paddle day. I’m not going to lie - I think all three of our spirits were crushed and we took turns struggling throughout the day. To make the last lock-opening of the day, the support boat motored ahead and left us to paddle the last 10 miles (we could portage our boards around the lock), which took about two hours. During that unsupported section of our paddle, I was pleasantly surprised to see my family standing on the canal bank cheering us all on, and that was just the energy boost that we all needed to finish out our day.”

The final approach. | Photo: Logan Graham

The final approach. | Photo: Logan Graham

“Our 4th and final day started off great - the wind died down and we were paddling with the discharge current. Then, about an hour in, we encountered blinding rain and the wind picked up out of the northwest. At first, we were able to hug the lee of the sea walls to shelter from the wind but, as we approached Pine Island Sound, we ran out of shelter and had to angle towards Sanibel Island, instead of taking a direct heading to our finish line at Fort Myers Beach, which added about seven miles to the end of our route. After navigating through Hurricane Ian debris and super rough waters in the Gulf of Mexico, we landed on the beach at the Pink Shell Resort, and were greeted by our friends and family.”

Through it all, Jake says “the best part of this adventure was our team - both the paddlers and support crew. Captain Robert, Big Doug and our photographer, Logan, made sure we were ready for anything, providing everything from fresh espresso to back rubs!”

Would he paddle it again? “Yes” Jake says, “I would definitely do it again, but probably on a longer time frame. Paddling 20 to 30 miles a day would be much more enjoyable.”

He also began thinking about “a way that we could get more paddlers involved to help fight this battle” and decided “let’s make it into a race!” So, he did.

The inaugural Lake 2 Ocean paddle race - “a fun and challenging 36-mile journey to help Rescue the River of Grass, to raise awareness about the toxic Lake Okeechobee discharges that are harming our beloved waterways and support local non-profits that are leading the battle for clean water” – will begin at the Port Mayaca locks, on the east side of Lake Okeechobee and finish in Stuart on Saturday, April 12th, 2025.

The race is open to paddlers of all levels on stand-up, prone or sit down crafts, paddling solo or in three-person relay teams. Paddlers will have to arrange their own drop off and pick up transportation, and portage around the St. Lucie locks, and everyone will be responsible for their own hydration and nutrition. There will be checkpoints and safety vessels along the course, and paddlers will have ten hours to complete the course.

|

|

Celebrations on a solid finish. | Photos: Logan Graham

Jake says: “By participating in this event, you’ll be supporting efforts to prevent further pollution, advocate for sustainable water management practices, and promote the health and well-being of our local ecosystems.” Proceeds from the event will benefit Friends of the Everglades, a Stuart-based organization founded by Marjory Stoneman Douglas that has been fighting to protect the Everglades since 1969.

This is an opportunity for you, dear reader, to become part of this movement. As Eve Samples, Executive Director of Friends of the Everglades, said “This paddle race puts a much-needed spotlight on Florida’s flawed water-management system by tracing the flow of harmful Lake Okeechobee discharges to the St. Lucie Estuary and Indian River Lagoon. Awareness is critical to advancing the well-known and achievable solutions needed to Rescue the River of Grass.”

Why is Jake doing all this? “What really drives me is the thought that, if these water quality problems continue, my children may not be able to enjoy our local waterways or the Everglades like I have. As I write this, we have blue green algae building up in the Manatee Pocket (a cove in Stuart) from the Lake O discharges that began a month ago.”

When you’re a man on a mission, motivation matters.